Embroidery in Metal: Reimagining Chinese Needle Art in Jewelry

ZOLANJEWELRYCompartir

Imagine an old Jiangnan courtyard: candlelight flickers on the silk, and a skilled needlewoman guides a thread into a petal—her hands moving with a tempo refined by generations.

Now imagine, centuries later, a similar light falling on a craftsman’s chisel in our workshop as he “traces” that same peony upon a sheet of pure silver. Space, material, and implement have changed, but the devotion—the slow, exacting concentration that transforms idea into form—remains unchanged.

This is the lineage we pursue: the translation of Chinese embroidery into metal embroidery, a continuum from soft fabric to enduring metal.

At ZolanJewelry, we do not simply copy textile motifs into metal; we honor the spirit of needle art and reimagine it through techniques of filigree, chasing, repoussé, and micro-setting. In doing so, we expand the taxonomy of Chinese textile art—transmuting private craftsmanship once known as nühong into public, wearable expressions of cultural continuity and contemporary design.

I. From “Nühong” to “Gongqiao”: A Cultural Recasting

In traditional Chinese society, embroidery was often referred to as nühong—women’s craft; it was intimate, domestic, and bound to rites of refinement. Yet the essence of that practice—patience, discipline, and an aesthetic of line—has always contained the potential for greater public articulation. When we speak of transforming embroidery into jewelry, we are engaged in a cultural recasting: turning private ritual into public art, turning “female handiwork” into gongqiao, refined technique recognized across audiences.

This shift is both technical and philosophical. Technically, we map stitches to chisels, threads to wires, and seed beads to gemstones. Philosophically, we liberate the role of the craftsperson—no longer confined by gendered categories—so that the quiet labor of handwork becomes an audible voice in contemporary design and cultural confidence.

II. The Philosophy of Softness and Strength

Chinese aesthetics often privilege the interplay of opposites—yin and yang, soft and hard, yielding and resolute. The maxim rou neng ke gang (“the soft can overcome the hard”) is not just poetic; it is a practical design proposition. Water cuts stone, and gold, though innately rigid, can be drawn into wires finer than silk. In our practice of metal embroidery we deliberately pursue this paradox: to make metal sing with the cadence of thread.

When a gold wire curls like a ribbon, when a silver surface displays the gradations of satin, we are not tricking the eye; we are expressing a deeper truth about material transformation. The jewelry becomes a theatre where softness is staged inside strength—and in that staging, Chinese fabric aesthetics find an unexpected, durable form.

III. Threads and Lines: Structural Parallels

At a structural level, embroidery and jewelry share the same visual grammar.

An embroiderer builds depth through stitch density and color gradation; a jeweler sculpts depth with line, relief, and set stones. Both operate through rhythm—repetition and variation—to suggest light, shadow, and movement. We often say: “Embroidery is three-dimensional imagination on a two-dimensional plane; jewelry is two-dimensional refinement within a three-dimensional body.” This apparent inversion is precisely where creative potential arises.

Consider a Su embroidery lotus: a thousand short stitches combine to create the illusion of a rounded petal. In metal, that illusion might be achieved with closely laid filigree wires, a chased ridge, and a subtle repoussé beneath. The viewer experiences the same volumetric suggestion, even though the medium differs.

IV. Craft Decoding: The Needle’s Logic in Metal

Translating needlework into metal demands precise correspondences between stitch types and metal techniques. We treat this mapping not as an intellectual exercise, but as a practical grammar for design and fabrication.

1. Chasing as Running Stitch

Chasing uses chisels and punches to create lines and textures on a metal surface—analogous to the running stitch in embroidery. Different-shaped chisels correspond to different needles: flat chisels produce uniform outline strokes like a flat stitch; rounded punches create dotted textures akin to seed stitching. This is a “subtractive” act of making: one careful incision determines the read of the line, and a single error can undo hours of work. The discipline required resembles calligraphy—the groove’s depth, the wrist’s pressure, and the pause between strokes together shape the “brush” of the metal.

2. Filigree as Woven Thread

Filigree is perhaps the most direct kin of embroidery in the metal realm. We draw gold and silver into threads finer than human hair, then weave and solder them into patterns that read like lace. Techniques such as twisting, looping, and overlaying recall embroidered couched-gold and raised stitching. The effect is a “no-ground” lightness—the metal appears to float, producing a feeling of transparency similar to the “透底” in textile craft.

Note the practical subtlety: creating filigree demands “hundred refineries”—from melting and drawing the wire, to annealing and shaping, then to the exacting work of joining and finishing. Each step requires absolute control of temperature and time; each loop must maintain rhythm or the pattern loses its musicality.

3. Inlay as Beadwork

In embroidery, beads and spangles create focal highlights. In jewelry, gemstone setting performs this role. Micro-pavé resembles dense beadwork; a bezel or prong setting that holds a central jade or opal functions like an appliqué patch on cloth. The contrast of a polished stone against a textured metal ground reproduces the same pictorial emphasis that an embroidered appliqué achieves on silk.

4. Repoussé as Relief Embroidery

Repoussé, working metal from the reverse to form relief, recreates the tactile bump and shadow of raised embroidery. Where an embroidered motif might ascend above its ground through padding and dense stitching, repoussé achieves a similar volumetric effect by shaping the metal from beneath. When combined with chasing and filigree, repoussé endows a piece with true relief—an interplay of surface and depth that reads as “needlework in three dimensions.”

V. Surface Treatments: The Illusion of Color and Thread

Metal is inherently monochrome, yet with the right finishes it can simulate the light qualities of textile. We employ a palette of surface techniques as if choosing thread colors:

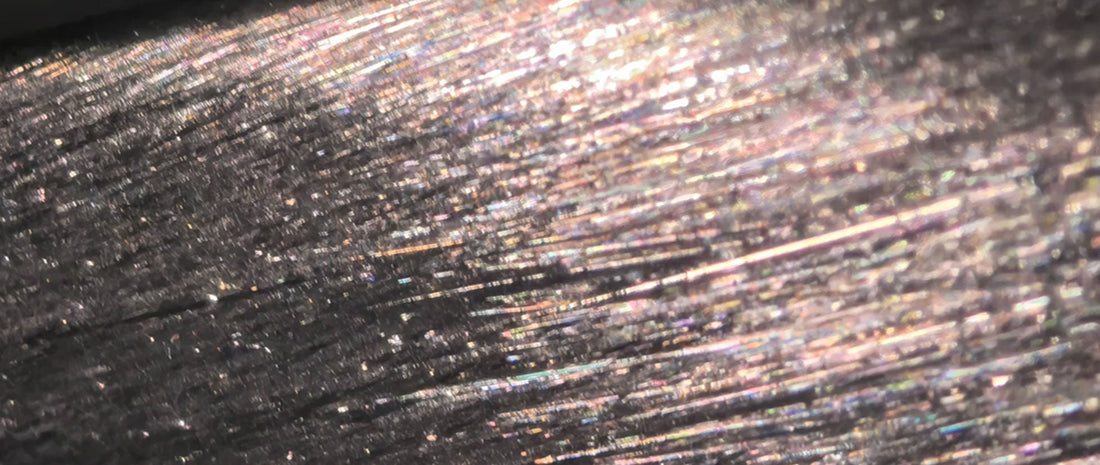

- Sandblasting — produces a soft, satin ground akin to matte silk;

- Mirror polishing — creates highlights like glints on a satin fold;

- Brushing / directional luster — guides light along a perceived thread direction;

- Rhodium / black gold plating — acts as dyed ground cloth, changing tonal contrast and making motifs pop.

Through these finishes we choreograph light and shadow just as a textile artist composes color and stitch, giving metal the illusion of woven luminosity.

VI. A Scene of Transmission: From Silk Room to Forge

To make the transformation vivid, we keep returning to the image of the Jiangnan court and the workshop: the same flame that warmed the sewing needle now tempers the silver wire; the same patient hands that once counted threads now measure solder joints. In our workshop, the Engraving chisel replaces the needle, and the rhythm of hammer and chisel becomes a kind of embroidery stitch. This scene is not romanticization—it is a literal continuation of craft spirit across time and medium.

We often tell visitors: watch an embroiderer and watch a goldsmith at work side by side, and you will recognize the same posture of attention. The stitch and the strike share the same moral economy: time, focus, care. In this shared economy lies the craft’s true inheritance.

VII. The Craftsman’s Ethos: Patience, Precision, and Temper

Both embroidery and high jewelry demand a temperament: calm, patient, and precise. The work is slow because quality demands slowness. A single misjudged hammer blow or overheated join can ruin a motif. The craftsman’s materials—wire, metal sheet, stone—require constant negotiation with fire and force. This negotiation is the crucible where the craftsman’s soul is revealed. We do not merely reproduce stitches in metal; we inherit the ethic of the needle: humility, attentiveness, and reverence for detail.

VIII. ZolanJewelry’s Micro-Embroidery Vision

At ZolanJewelry, we interpret Su embroidery—renowned for its painterly gradations and hair-thin stitches—into a practice of micro metal weaving. Our micro-embroidery pieces begin not as templates but as meditations on line. We translate the tonal subtlety of Su embroideries into gradations of wire density, layer depth, and surface finish.

Take, for example, a Bellflower brooch: the petal’s edge is delineated by chased lines (the “running stitch”), the inner texture built through filigree knots (the “seed stitch”), and the dew simulated by micro-set diamonds. Through these layered techniques we achieve an effect that reads like Su embroidery at arm’s length—but endures like a jewel for generations.

Elevate Your Look with Craft ↓

IX. Applications and Modern Resonance

Textile-inspired jewelry extends beyond aesthetic novelty. In contemporary contexts—weddings, cultural exhibitions, editorial fashion—these pieces function as conversation objects: symbols of cultural literacy and personal taste. We also craft engagement pieces that incorporate traditional motifs—dragons, phoenixes, peonies—reinterpreting their symbolism into forms suitable for everyday wear.

Customization plays an essential role: customers request family motifs, ancestral patterns, or color palettes inspired by heirloom textiles. Through bespoke commissions, the lineage of textile craftsmanship becomes personalized narrative—an heirloom reimagined for the modern body.

X. Conclusion: The Eternal Thread

Metal embroidery is not a fleeting trend; it is a way of thinking about material, time, and cultural continuity. By reimagining Chinese fabric and needle art into filigree jewelry and metal relief, we are not abandoning textile tradition—we are extending it into a new material future. This is the soft revolution in metal: a practice where patience refines form, where a stitch’s logic becomes a line’s eloquence, and where the quiet rooms of the past enter public cultural conversation as luminous, wearable art.

In our hands, silk’s memory is preserved; in our metal, the thread’s intent endures. This is the promise of Chinese textile jewelry—to hold memory, craft, and beauty in forms that are both tender and eternal.